The wrecking ball is coming to Winchester Road

by Janice Rice-Brother

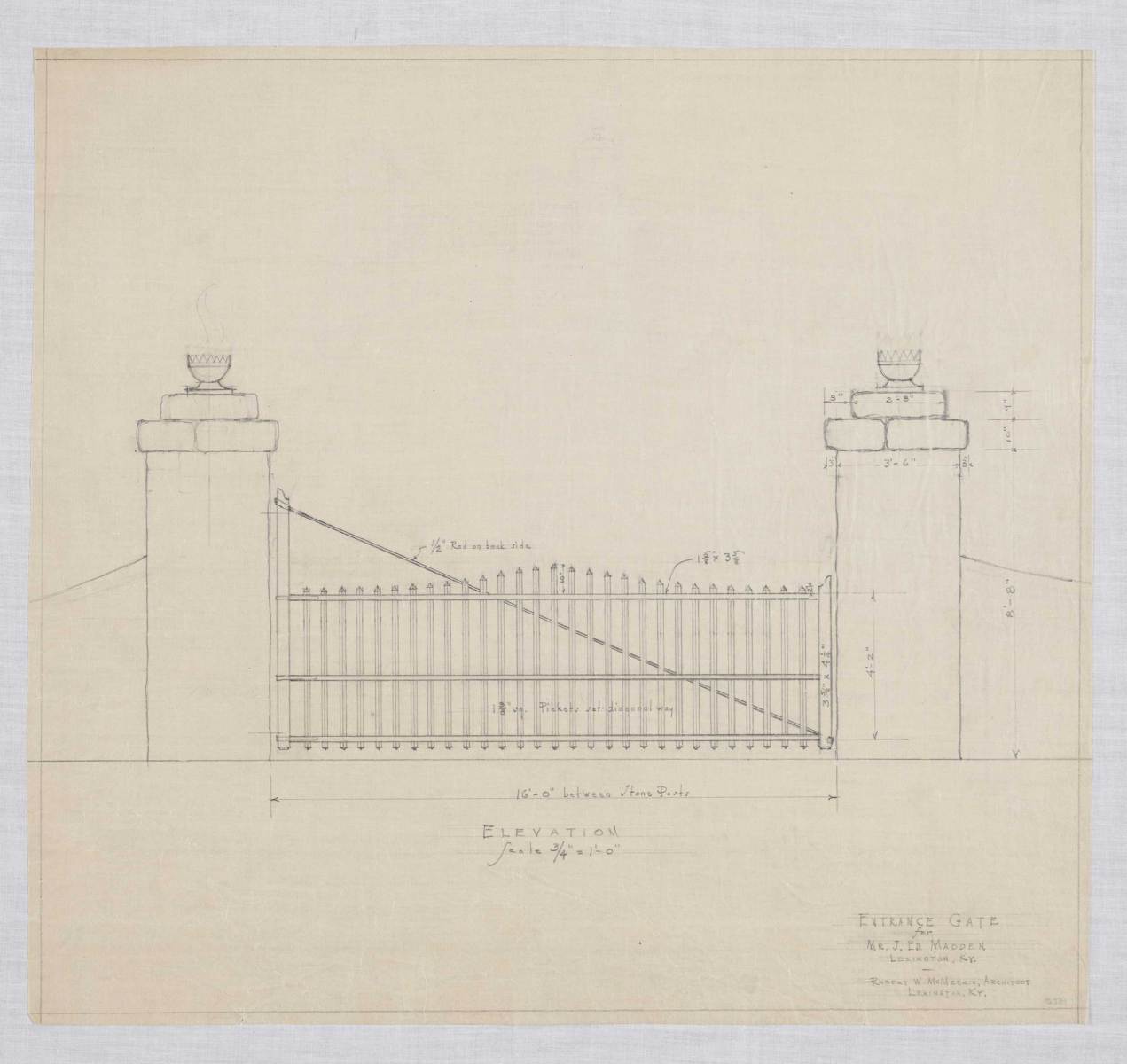

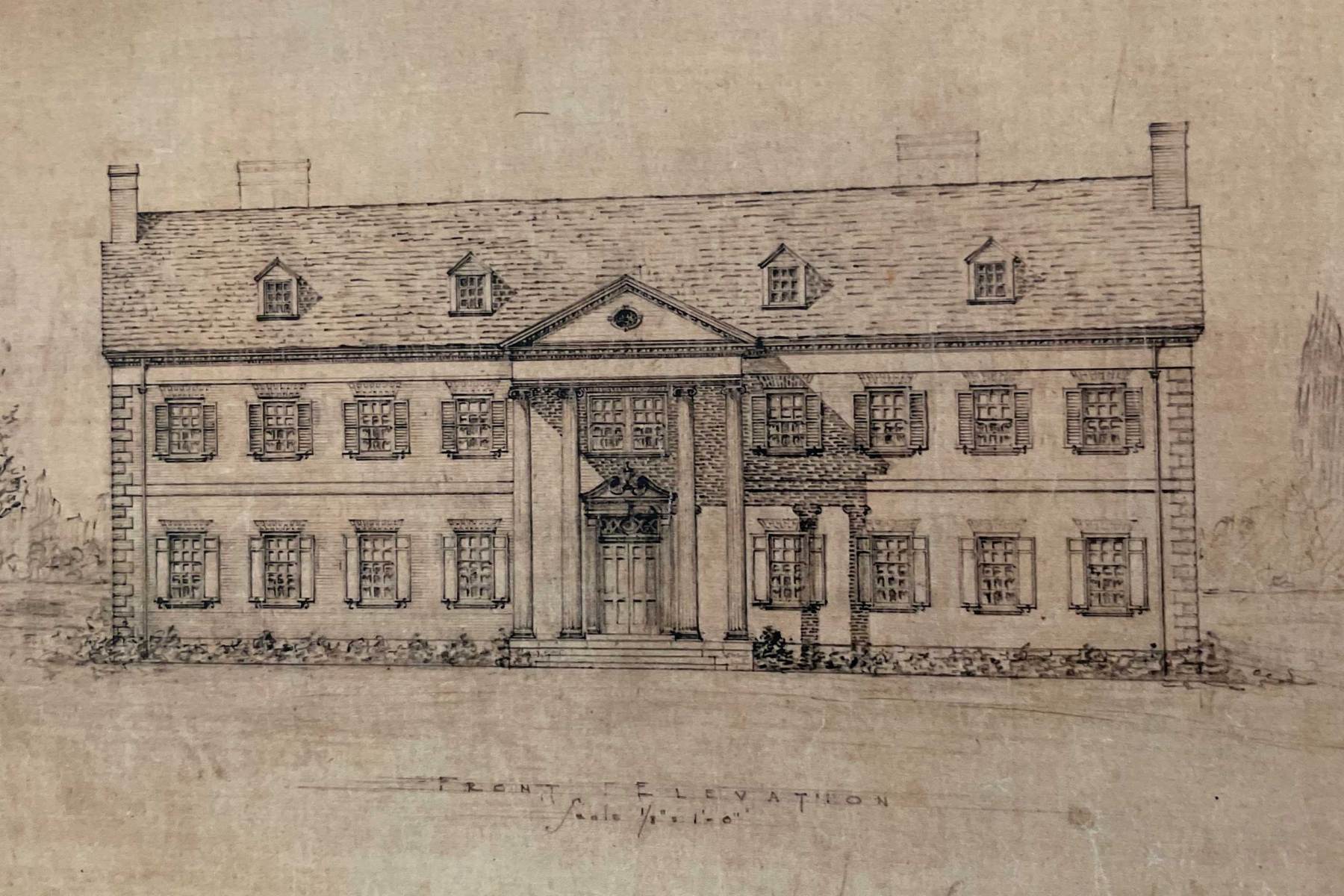

Stories and the people who created them enliven the most basic of buildings. Sometimes, of course, stories of personal tragedy envelop a structure like a cloud, and that cloud overshadows the most elegant and masterful of designs. So it is with Meadowcrest, an imposing Neo-Georgian house designed by prominent local architect Robert McMeekin in 1931. Built for one of the heirs to the farm known as Hamburg Place, the three-story brick mansion will soon be demolished.*

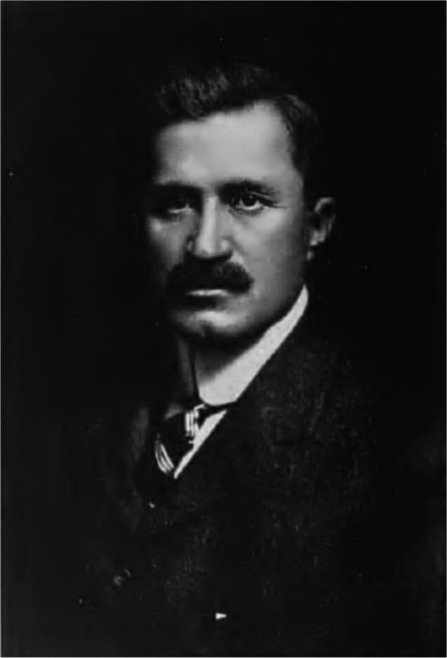

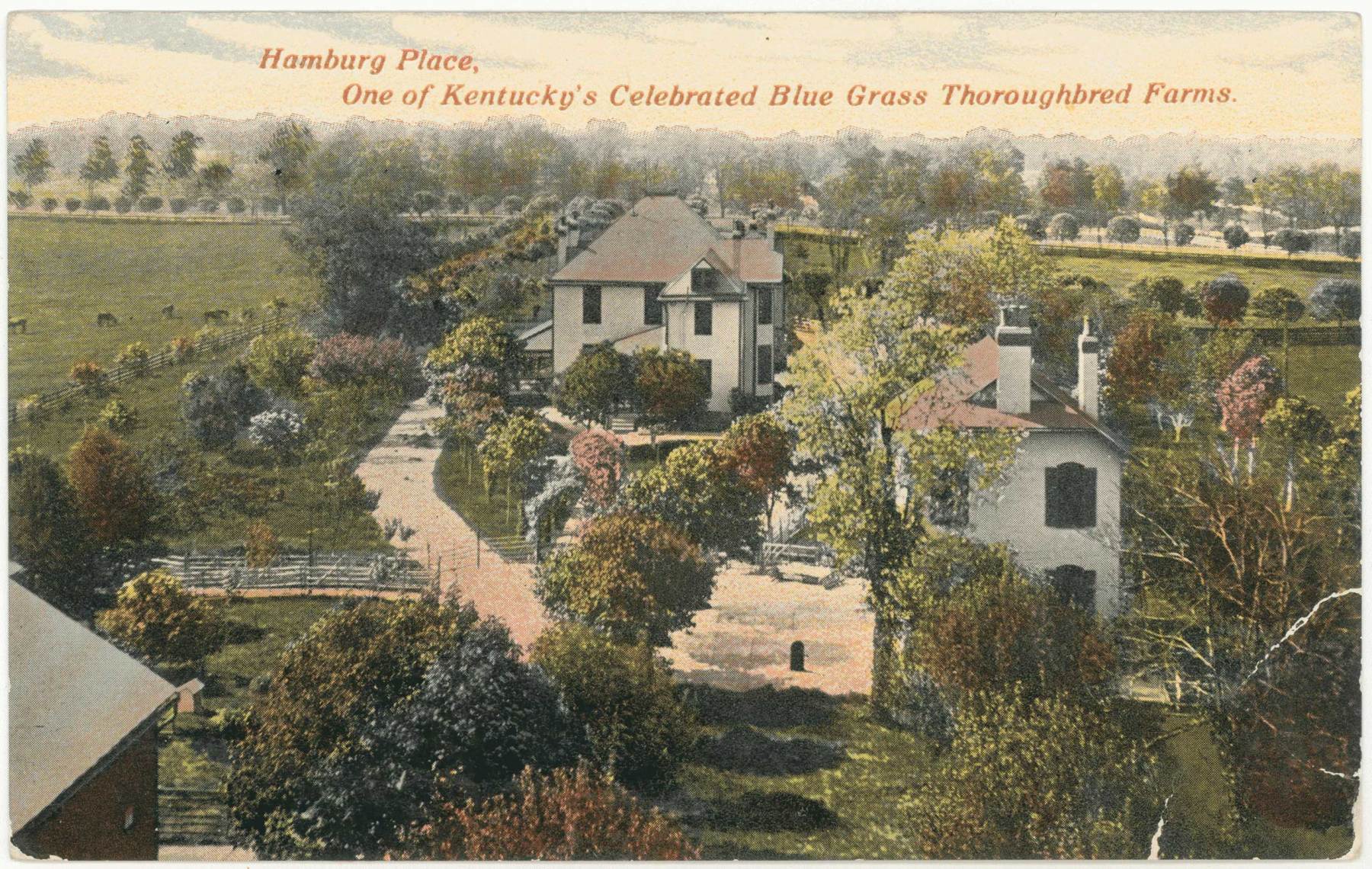

Long before “Hamburg” was shorthand for shopping, it was a fabled early 20th century horse farm. The founder, John E. Madden, was a newcomer to the Bluegrass, arriving in Lexington in the last decade of the 19th century.

His skill at training and selling horses for a considerable profit allowed him to purchase over 200 acres of land east of Lexington on the Winchester Road (US 60). That initial purchase grew to over 2,000 acres, and as the land that Hamburg Place occupied expanded, so did Madden’s fame and bank account.

His personal life appears, through the eyes of a historian, less than stable and calm. I don’t want to speculate about someone else’s family – I certainly wouldn’t want folks dissecting the details of my ancestors, no matter how far removed I am from their existence. Even historic details still possess the power to wound. But the story of Meadowcrest can’t be entirely ignored nor completely separated from the house itself.

In 1964, Ruth Madden Maxwell and her sons were awarded $40,000 for the damages caused by Interstate 75 splitting the farm in two.

A rocky marriage, divorce (shocking in 1909!), and custody fights over his two sons (John Edward Madden, who went by Edward, and his younger brother, Joseph McKee Madden) possibly sowed the grounds for later tragedy in the family.

The younger son, Joseph McKee Madden, attended boarding schools and graduated from Princeton in 1920. He and his brother did not follow their father into the horse industry, but instead helped develop the fledgling oil industry. Later, Joseph Madden invested in a corn products company in Iowa, and married a local girl. They had two sons while living in Iowa.

But despite leaving Kentucky, the press remained most interested in the two Madden sons. When their father died in 1929, he left Hamburg Place and a fortune to his sons.

Edward Madden moved into the original house at Hamburg Place after their father’s death. Joseph remained in Iowa.

In August 1931, the Lexington Herald announced (on the front page) that Joseph Madden was coming back to Lexington, and planned to build a “$400,000 mansion” on a part of Hamburg Place. The plans for the “palatial residence” were in the process of completion, and contracts for construction had been let.

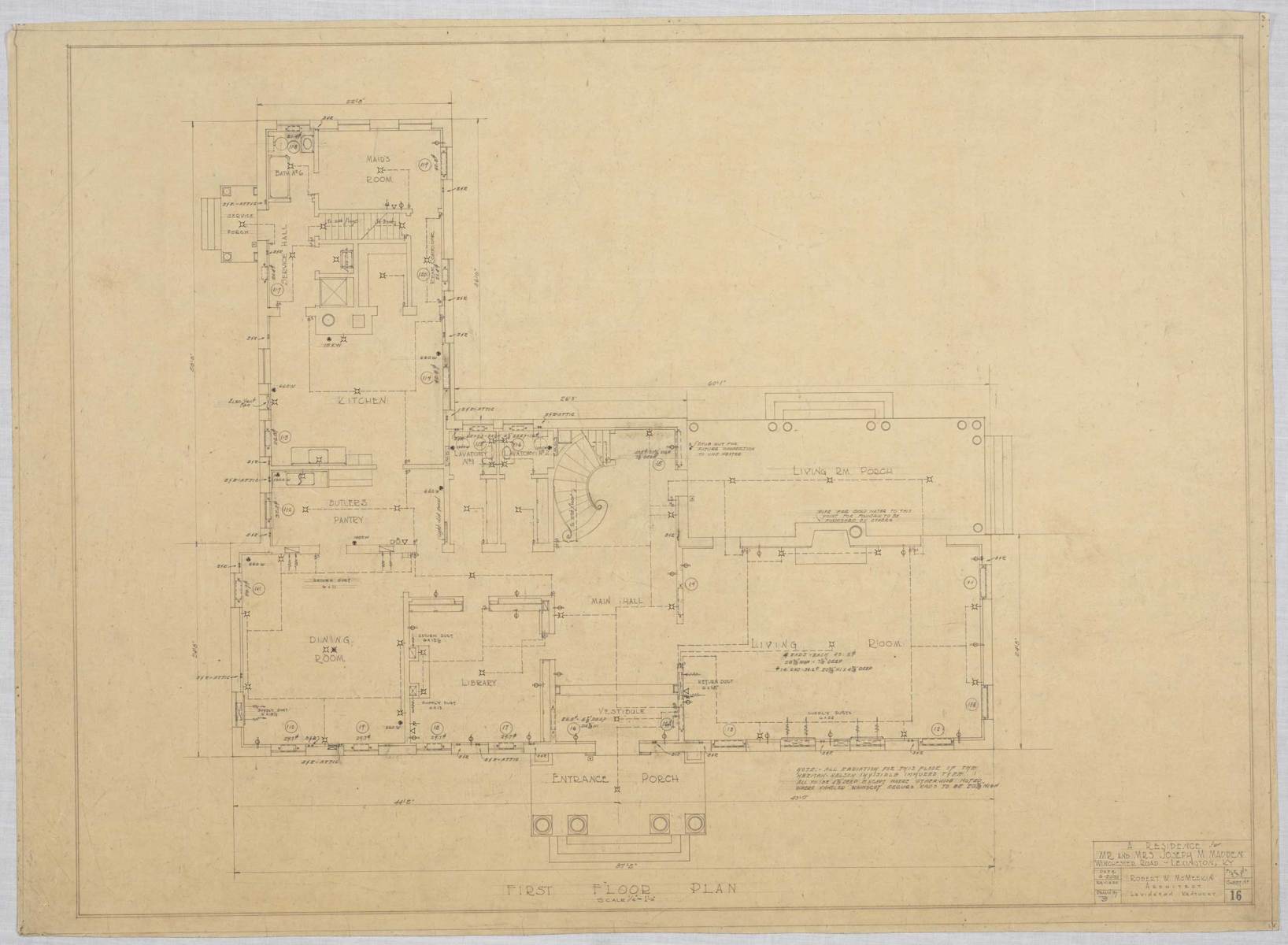

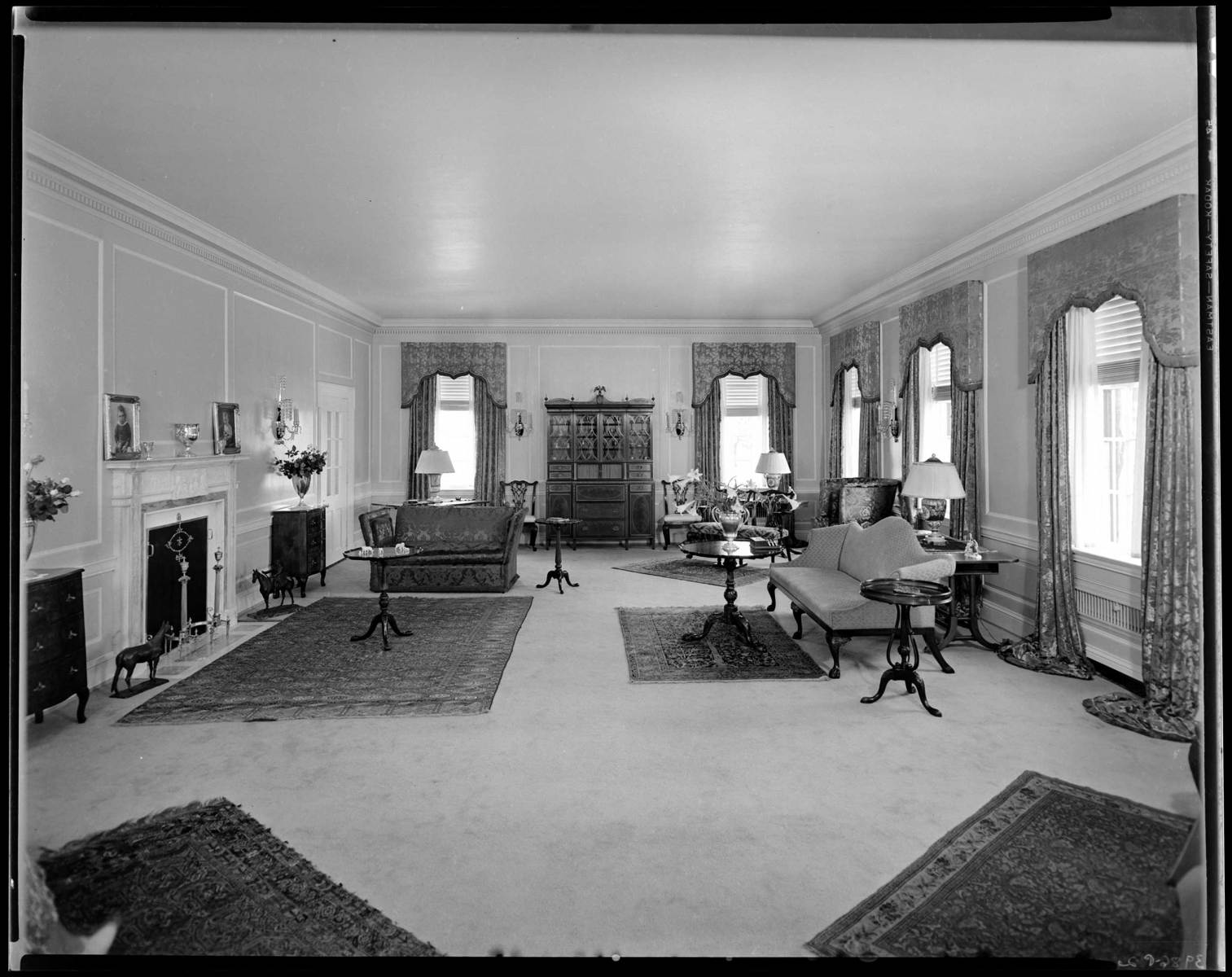

The house as designed contained “five master bedrooms, four servants’ rooms, living room, library, dining room, service rooms, gymnasium, tap room, seven bathrooms and five lavatories. ” An eight-car garage was built to the rear of the house. The plan is fairly traditional, with a central hall and one room (more or less) to the side of the central hall. The main block of the house is only one room deep.

The house was extolled as “fireproof!” and a two-story portico graces the facade. The portico shelters the main entry, which leads into the main hall, which runs the depth of the house and features a circular staircase. A living room extends to the right of the hallway, and the library and dining room are located to the left of the entry. A butler’s pantries, kitchen, lavatories, and service rooms are located in the ell that extends to the rear of the main block of the house.

The exterior is restrained yet stately, with a quiet elegance. Stone quoins detail the corners of the house, and the facade (nine bays wide) seems to stretch on for days.

Winchester Road was a rural thoroughfare at the time. I imagine that the construction of such a large – and costly – house (most folks were still in the throes of the Great Depression) garnered much attention. The Madden sons were wealthy, privileged, good-looking, and seemed set for life.

Joseph Madden never lived in Meadowcrest. On October 31, 1932, he committed suicide in a sporting goods store in New York. He left behind his wife, Ruth Rovane Madden, and two sons, ages three and eight months.

Suicide haunts the survivors. I know this from my own family experience. What happened to Joseph Madden – and later to his older brother – is devastatingly sad.

Ruth Madden, most unexpectedly a young widow, moved into the house with her two young sons. How could that not have been an emotional struggle? But she lived at Meadowcrest the rest of her life.

Her brother-in-law, Edward, bought most of the farm from her. Ruth Madden retained Meadowcrest and around 100 acres.

Meadowcrest is a beautiful house. Its interior, I am told, retains much of the elaborate detail that defined it when built. The design is superb, and the setting was exquisite. There’s not much better than a Bluegrass farm (I’m biased, since I live on one).

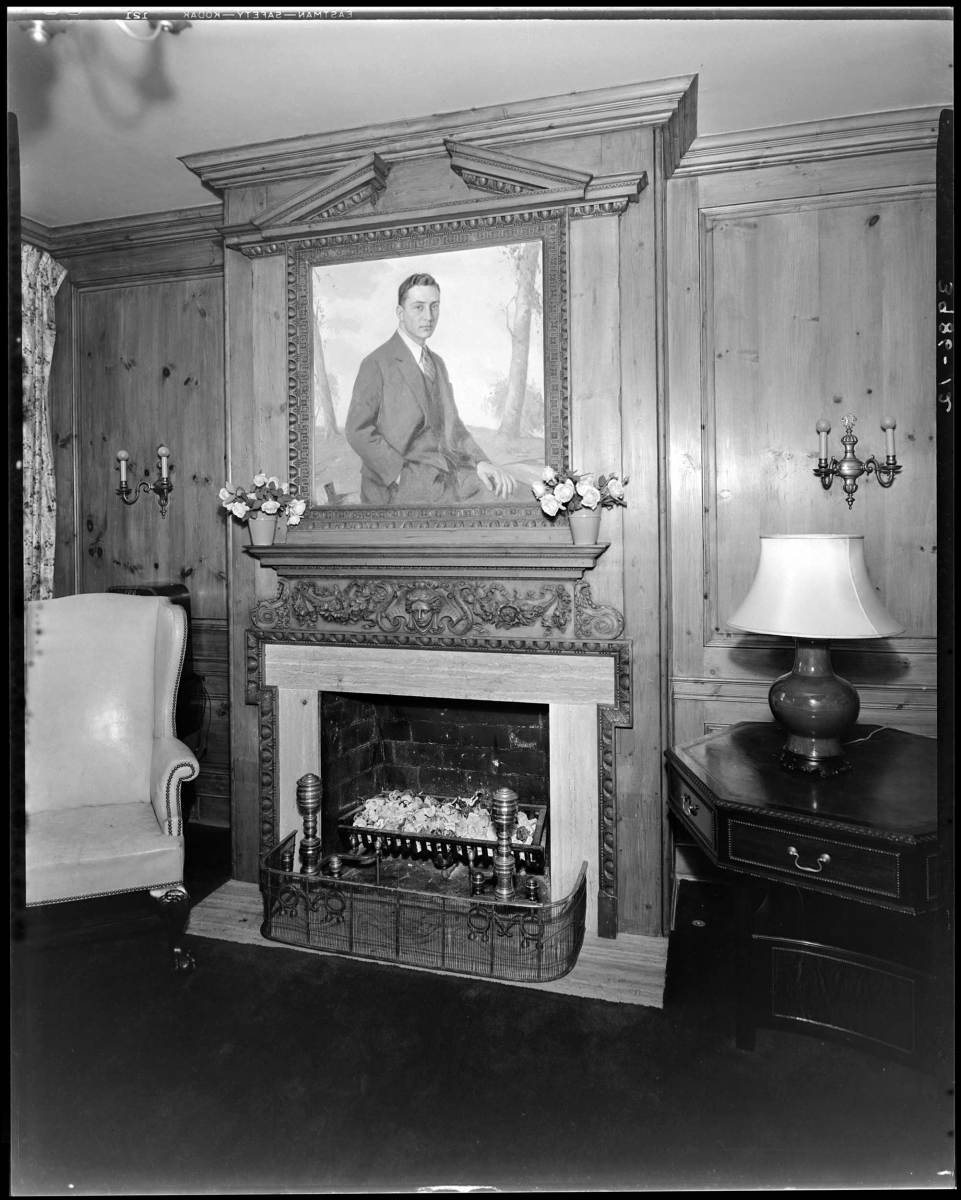

Ruth and Joseph’s two sons lived there intermittently (from what I can discern), and operated it as a horse farm. A fire in 1952 destroyed the library where Joseph Madden’s portrait hung over the fireplace.

But the rural nature of Fayette County was changing. The transportation industry, energized by the advances of technology, was chewing up and spitting out pastoral landscapes and neighborhoods across the country. In 1964, Ruth Madden Maxwell (one of her subsequent remarriages, and I hope a happy one) and her sons were awarded $40,000 for the damages caused by Interstate 75 splitting the farm in two.

Sadly, the foray of highways was just beginning. The “pleasant country” as the environs at Meadowcrest were described in a 1938 article was irrevocably changed. The coming decades would usher in more and larger roads, increased traffic, and the casual consumption and destruction of Bluegrass land. The very land that enriched the foals and horses that made Hamburg Place famous in the horse industry was suffocated by asphalt.

Meadowcrest stayed in the family until the end of the 20th century. The house was an icon for many – a movie was filmed there in the last decade. Rumors about the abandoned stately building circulated every so often. I admit I only listened with half of an ear – my taste runs to earlier forms of architecture, and this house never really interested me. And, without knowing the story behind its construction, I always thought it was a sad looking house.

I watched (with dread) the creep of pavement, shopping centers, vinyl clad houses and apartments all across Central Kentucky. Lots of money was being made, but at what cost?

My daughter asked me, as we drove by Meadowcrest yesterday, on our way home to our family farm and historic house (not palatial by any means), why the house had to be torn down. “The almighty dollar,” I replied, repeating a phrase my father used often to describe the loss of farmland and its development.

There’s no silver lining in this story. A well-built, beautiful house will go to the landfill. The farm will be paved over. The march of development will continue down Winchester Road, until it too is a route I hate to take. Rest in peace Meadowcrest. Both the beginning and the end of your story are not as they should be.

*A demolition permit has been filed with the Lexington-Fayette Urban County Government by the current owner. The property will be developed (I assume) when the house is razed. Building inspection records are available to the public online.

This article also appears on pages 8 & 9 of the February 2022 print edition of Hamburg Journal.

For more Lexington, KY, Hamburg area news, subscribe to the Hamburg Journal digital newsletter.

To advertise in Hamburg Journal, call 859.268.0945